Our expert team at Colloide Engineering have compiled a list of your most frequently asked questions on district heating network systems and answered them all below. We will continue to update this page as the energy and renewable sectors progress towards net zero targets and innovation continues with district heating technologies. The go-to place for all your district heating queries. If you have a question that we have not yet covered, please feel free to let us know by emailing [email protected].

What is a district heating network?

A district heating network also referred to as a heat network, refers to any heating system which uses a common heat source for use by multiple users. Some systems use conventional gas boilers while others may capture energy released as heat from various or renewable sources. This is then processed within a centralised location such as an energy centre and is distributed through highly insulated pipes to numerous users such as residential or commercial buildings, providing them with heat and hot water.

What is a district cooling system?

District cooling systems are advantageous, as they are environmentally friendly, yield lower lifecycle costs, are reliable, decrease building costs, and provide architectural flexibility.[1]

District cooling systems are somewhat identical to heat networks and the two can work in tandem. Similar to a district heating network, in that they have one centralised source for several buildings, delivered through a network of underground pipes. The distinct difference is that district cooling delivers chilled water to buildings in order to provide indoor cooling.

Discover the innovative Bunhill 2 Energy Centre that has a combined district heating and cooling system. Where the heating is delivered to local housing and cooling is delivered to the London Underground.

How does a district heating system work?

District heating offers the promise of a neat solution for the supply of low-carbon heat to homes, businesses and public buildings.

Hot water is pumped from the Energy Centre to the Satellite plantrooms of the User where a substation transfers the heat to the local distribution system, splitting the load to be delivered to Space heating and Domestic hot water circuits. The relatively cold return water from the plantroom is then sent back to the Energy Centre to be reheated at the beginning of the cycle.

A district heating system can be used to provide Low Temperature Hot Water (LTHW) for residential or commercial buildings and in some industrial cases, High temperature and steam systems are supplied by a District Network. The idea is to provide low-carbon energy cheaply. If the central heating generator is a renewable technology, and ‘waste’ heat is incorporated from other sources, it can be a highly efficient and green heating option. The use of one common heat source has an economy of scale when it comes to end user cost.

The heat source might be a facility that provides a dedicated supply to the heat network, such as a combined heat and power plant; or heat recovered from industry and urban infrastructure, canals and rivers, or energy from waste plants.

Is District Heating expensive?

It is a common misconception that district heating is an investment expensive technology. District heating, to a large extent, is able to compete with individual heating, when establishing a new heat supply. This is because the district heating system requires lower production capacity, uses cheaper fuels and is more efficient to such an extent, that it offsets the heat loss in pipes and the establishment costs of the grid. Another advantage of district heating is, that in some areas it will be possible to take advantage of surplus heat from nearby industry, which is useable in district heating, but not in individual heating solutions. In the cases where these advantages are large enough to offset the heat loss in the district heating grid and investment in that same grid, district heating will be the obvious choice. In areas where the population density is too low (too big a district heating grid) or there are no cheaper heat sources available, establishing district heating will not be cost efficient and individual heating will in these cases be the obvious choice. [4] The common misunderstanding that District Heating is an expensive solution perhaps arises due to the fact that investment costs are typically funded by one identity instead of all house owners connected to the network, as it would be in the case of decentralized heating solutions.[5] Overall, district heating is an important player in today’s heat and energy markets and also in the future.

How many district heating schemes are there in the UK?

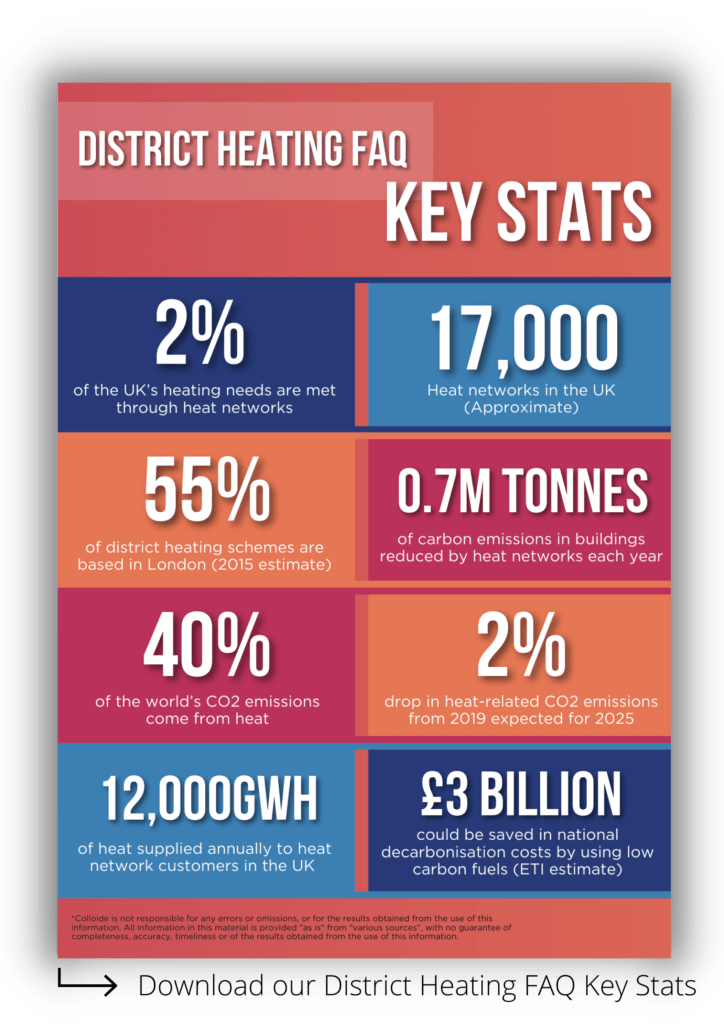

Only 2% of the UK’s heating needs are met through heat networks. Approximately 17,000 heat networks in the UK supply around 500,000 customers, including 445,517 domestic homes, with approximately 12,000GWh of heat annually [6]. It was estimated in 2015 by the Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy that 55% of district heating schemes were based in London. Although district heating is making its mark within the UK, these figures are not surprising given the low penetration of district heating networks within the UK compared to across the globe. Check out ADE’s fantastic District Heating Installation Map showing Universities, Hospitals and Residential/Commercial district heating installations in the UK.

Image Caption: © 2021 The Association for Decentralised Energy, 6th Floor, 10 Dean Farrar Street, London SW1H 0DX. Registered in England #917116.

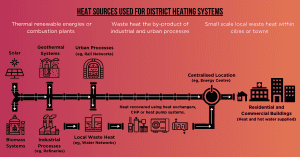

Heat sources used for district heating systems

District heating can be fed by various heat generation sources:

- Heat produced by thermal renewable energies or combustion plants such as biomass, geothermal systems or solar thermal arrays.

- Waste heat the by-product of industrial and urban processes (cement industries, refineries, food processing, chemical industries, Underground Rail Networks etc) can be recovered using heat exchangers, CHP or heat pump systems.

- Small scale local waste heat within cities or towns from the likes of data centres, manufacturers, water networks, sewers and subway tunnels.

Why is district heating important?

District heating is important, as it has a vital role to play in the clean energy transition. 40% of the world’s CO2 emissions come from heat [7] and the EU has over 300 TWh/year of waste heat potential, with almost 30 TWh/year from the United Kingdom alone.[9]. District heating can certainly combat these statistics, offering an alternative way of lowering emissions, making use of an otherwise wasted resource and thus moving away from a reliance on fossil fuels. Without a significant change in non-renewable heat consumption, total heat-related CO2 emissions in 2025 are expected to be only 2% lower than in 2019. [8]

There is certainly a growing case being made for the expansion of heating networks. A recent report from the Energy Technologies Institute (ETI) suggested that by using low carbon fuels they could potentially meet nearly half of UK heat demand while reducing national decarbonisation costs by £3 billion.

Benefits & Limitations of District Heating Systems

Advantages

Heat networks reduce carbon emissions in buildings by approximately 0.7 million tonnes of CO2 each year. [6]

Captures heat that would otherwise be wasted, e.g. from power stations, data centres and large industrial sites.

Long-term price stability by accessing local waste heat sources.

Can tackle fuel poverty and reduce housing management costs.

Aid the transition to lower carbon heat sources.

Disadvantages

Little protection or control for consumers living in properties connected to district heating networks.

Consumer prices need to be more competitive with alternative heating costs.

Demand management must be improved to provide better thermal dispatch.

Difference between communal and district heat networks

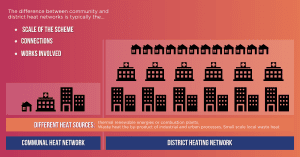

It is common within the energy industry for the definitions of communal and district heating networks to be misunderstood or confused. “Heat Network” seems to be used within the industry as an umbrella term for both communal and district heat networks, as well as for heat network infrastructure in its entirety from energy centres to pipework.

The difference between community and district heat networks is typically the scale of the scheme, connections and works involved. District Heat Networks tend to distribute heat from large-scale generation and waste heat sources to wider areas than community heat networks. They do this by connecting with community schemes, normally through large pipes laid within the ground.

Community Heat Networks on the other hand are more centralised to one or a few local buildings and help in supplying heat and hot water through a series of pipes generally within the premises.

For example, in the Bunhill 2 District Heating System, the Energy Centre generates heat from Moreland Street and circulates the heat as far as Bath Street (near Old Street Station). The pipework connects a number of dwellings and estates such as Rahere House, Ironmonger Row Leisure Centre and Godfrey house.

While Rahere is connected to the Bunhill District Network it forms part of the Kings Square Community Network, sharing its heat with President House and the new Kings Square extension. Godfrey House has its own Community network connecting it to Newland, Patterson and Bath houses.

Is district heating regulated?

A number of years ago Heat Networks accounted for only a small proportion of UK heating systems. As a result, their locations were unrecorded, and their operation was unregulated until 2014 [2]. The Heat Network (Metering and Billing) Regulations (HNMBR) which came into effect in 2014, require operators to submit a notification to the Office for Product Safety and Standards (OPSS) for the heat networks under their control and where necessary, install metering devices. Under the HNMBR a heat network must:

- Provide a shared source of heat for multiple users

- Water, steam or chilled liquids must be the heat transfer medium, but the central heat source can use any type of technology

- The heat must be used for heating, cooling hot water or processes

- Heat suppliers must sell the heat to final customers

The HNMBR Regulations were subsequently amended in 2015, and most recently, in November 2020. Find out more information and guidance for heat suppliers on https://www.gov.uk/guidance/heat-networks

Until recently, there was no regulator for heating networks, as there was for electric and gas networks (Ofgem), meaning consumers on a District Heat Network had less security than traditional gas and electric consumers. This meant there was no ombudsman to receive complaints, which might have discouraged consumers from connecting to a heating network. [9] However, the Government announced in December 2021 that it had appointed Ofgem as the heat networks regulator for Great Britain to ensure consumers receive a fair price and reliable supply of heat as we make the transition to net-zero.

Support for the district heating sector.

The Heat Network Delivery Unit (HNDU) has been one of the primary initiatives from the government that helps support local authorities in England and Wales in the early stages of heat network development. The Heat Networks Investment Project (HNIP) also supports public, private and third sectors to increase the number of heat networks, deliver carbon savings and help develop a sustainable heat network market. The HNIP has been extended until March 2022 which will then be succeeded by the Green Heat Networks Scheme fund. [3]

Given current statistics and the local nature of heat supply, an increasing number of policy initiatives are being developed at the subnational level, with cities and local governments using their regulatory and purchasing authority to encourage the use of renewables through municipal mandates for buildings or through their management of urban district networks. [8]

Sources:

[1] https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/B978012819556700005X (Energy Sustainability, 2020)

[2] https://www.gov.uk/guidance/heat-networks

[3] https://www.lawgazette.co.uk/legal-updates/regulatory-developments-on-heat-networks/5106195.article

[5] https://www.witpress.com/Secure/elibrary/papers/ESUS13/ESUS13009FU1.pdf

[9] https://www.mdpi.com/1996-1073/12/2/310/pdf

https://energysavingtrust.org.uk/what-district-heating/

https://www.thegreenage.co.uk/what-is-district-heating/

https://www.heattrust.org/resources/2-general/112-what-is-a-heat-network

*Colloide is not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of this information. All information in this material is provided “as is” from “various sources”, with no guarantee of completeness, accuracy, timeliness or of the results obtained from the use of this information.

Get in touch

If you’d like to speak to a member of the Colloide team, get in touch.

Colloide has a strong base of experience in providing renewable energy solutions to the agricultural, industrial and municipal sectors. This experience allows us to assist a range of organisations in becoming more sustainable through lowering their carbon footprint. Discover our full range of innovative technologies.